Interview with an award winner

TCAA 2024-2026

OH Haji

Photo & Video Documentation: Hiroyasu Shieh

Photo & Video Documentation: Hiroyasu Shieh

Sound: Kengo Yokoyama

Profile of OH Haji is available here

I think your current style of dyeing, weaving and unravelling, particularly the unravelling, is a process of breaking down shaped objects and you are doing the exact opposite of the techniques of dyeing and weaving in the manufacture of clothes et cetera – what is the background to this unravelling?

I majored in the Dyeing and Weaving course at Kyoto City University of Arts, then wove textiles using threads I dyed myself, made ethnic costumes with it and produced works using the motif of the chima jeogori that is the traditional costume of Korea.

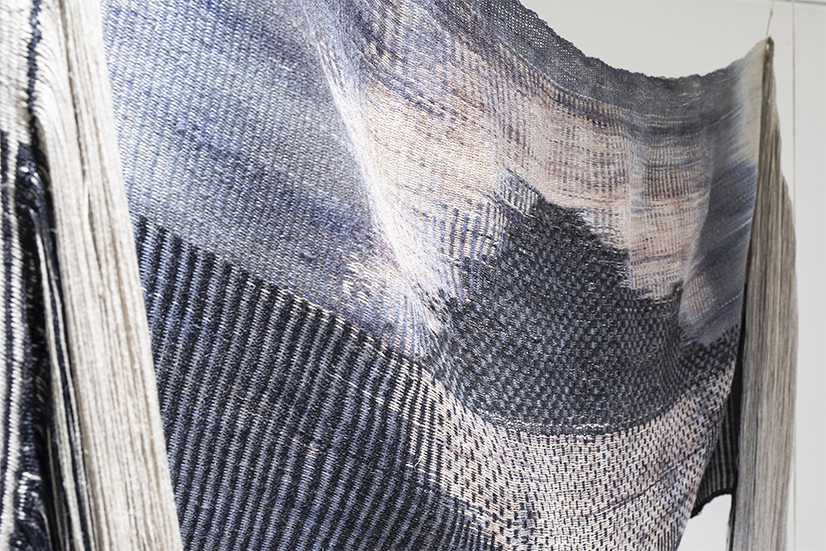

The textiles I weave use the Hogushigasuri (warp printing ikat) technique. This is a twice-woven technique in which the roughly woven textile is printed over and the once wove textile is then replaced on the loom and rewoven with the weft removed. By using this process, a textile in which there is a gap between the design and splashed pattern can be achieved.

In the course of using this technique to make ethnic costumes, an issue within myself came to the surface. While ethnic costumes perform the role of being clothes that enwrap people and are worn by them, they also have a representational nature at the social level. Of course, I was aiming to use that as a motif for my works, but I also felt that it was that representational nature that stood out boldly in the foreground. When I started to search for other approaches, I looked afresh at the Hogushigasuri technique I had been using. By weaving the textiles, printing on them and undoing the spaces between the threads woven at the time, with a textile dyeing and weaving technique in which the internal parts appear on the surface, the completed textile displays both the printed areas and the unprinted areas on its surface. I thought that structurally this is fascinating.

I thought that it is possible to show the parts that have not been interwoven, and using this technique I tried to unweave the textile, then undo and loosen the material, remake threads from that material, and started to create new works from them. I weave and then dismantle or unweave the textile by myself.

This is like the action of undoing a memory that has once attained a shape, or for example undoing something not interwoven, and trying to imagine what is there; that is what has led up to my present technique.

Using cyanotypes is a specialized way of creating works – how did you come to use them?

What sparked my use of cyanotypes was a workshop I held at which people used knitted mats called doilies brought from their homes. The doilies were brought by people so I wanted them to take them home as they were, but I also wanted to keep a record of them and arrived at cyanotypes while searching for a method to transfer the knitted doilies to textiles. Cyanotypes are also known as blueprints and are a photographic method in which film is transferred to light-sensitive paper, but when I found out that it was also possible to use the technique on textiles treated with solvents, I started to use the cyanotype method from that workshop onwards. When you treat the textiles with solvent and let it dry, then place the knitted material on top and expose it to sunlight, the parts treated with solvent undergo a chemical reaction.

If you then remove the knitted material placed on top and wash the textiles, the parts where a reaction occurred are left blue and the parts of solvent upon which the knitted material were placed and were therefore not exposed to the sunlight start to dissolve in water, leaving a pattern. I am currently using the cyanotype technique in the production of works based on archive photos.

Could you tell us about your main field of work and your career up to now?

The base of my work is exhibiting installation works at art museums and galleries. I lived in Toronto, Canada for one year from 2008 to 2009, where I worked as an intern at the Textile Museum of Canada; this gave me an opportunity to conduct research into the kasuri pattern ethnic costumes and textiles in the museum’s collection. I was able to look at all sorts of designs and patterns using the same technique from an array of different places, as well as the transmission of the technique. This served as the catalyst that made me start to become interested in researching various textile techniques and their backgrounds.

After that I was given the chance to research kogin-zashi embroidery kimonos in the collection of the Aomori City Board of Education for the exhibition of Aomori Contemporary Art Centre (ACAC), and experienced exhibiting my own works together with some from the collection. I found it fascinating to learn through a single dyed and woven textile work the reasons why, for example, this textile work is no longer produced, and felt that it would become a source of inspiration for my own creative activities.

I have tried to seize an opportunity to conduct research into what I’m interested in through dyed and woven textile works, and my interest in the dyed and woven textile works of the Andes is one such case.

The other thing I’ve been doing is workshops. I was contacted by the Breaker Project based in Nishinari in Osaka, and for two years I held workshops in the community about unravelling knitted material. I held a reading workshop at the Art Tower Mito. Personally my workshops are in a parallel relationship with my installations, and I feel they both play the same role. By experiencing the processes, the viewers and participants are given an opportunity to widen their imaginations, and as chances for them to trace back through their own memories I am doing them side by side. I create works incorporating in my installation what arises in the process of the workshops, and based on my research into archives.

Were there any comments from the selection committee of the TCAA during the final screening, award ceremony and symposium that left an impression on you?

At the symposium, I was amazed when one of the selection committee members told me that I had created works such as those about the memories of my grandmother and continued to create works of the Grand-mother Island Project. Doing all of these under the theme of the memories of preceding generations involved a sense of contemporaneity. That is something I myself have an interest in, and the fact that my work is being seen as being on the same timescale was a discovery for me and I was really pleased to hear such a comment.

Furthermore, I am always thinking in the creation of my works about universality and the nature of being a person involved, and hearing that this is something that the selection committee discussed made me feel again how important it was that I had agonized over this question while creating my work.

As of the recording of this interview (July 2024), you have come to Japan for your first overseas activity – did you make any discoveries during your stay?

Having been given this opportunity I went to the Osaka Korea Town Museum in Ikuno, Osaka. I was intrigued that such a museum had been established in a place that I had often visited since childhood. There is the Korea NGO Center in that neighborhood, which is involved in things about Japanese-Korean relations and activities aimed at young people. I was able to listen to stories about their activities, and I think this served as the motivation for the research that I am planning to conduct on Jeju Island in March 2025.

In addition, a collection of literature concerning relations between the Korean Peninsula and Japan, collected privately by a Zainichi Korean (a Korean residing in Japan) through their own funds, has been donated to the Kobe Municipal Chuo Library, and there is a library in which an entire room has been devoted to the Seikyu Bunko (the name of the collection of books) for people to peruse as they wish. The literature in the collection includes documents in Japanese and Korean, some quite old documents, academic pamphlets published in South Korea, and documents that it would otherwise be difficult to gain access to in Japan for those who are not part of the Zainichi Korean community. I stayed several days in Kobe this time and often visited the collection. There was a collection of books that coincided with my own interests and I picked up and pored through the ones that intrigued me. I believe that being given that time enabled me to pass time that served as a starting point, not only for my next work, but also the work I will approach on this theme over a long period.

Elsewhere, I had long wanted to see the landscape of the harbors where the Ama divers (women who dive for shells and other marine life) work and live, so I spent a few days on Tsushima Island. I had read literature about them, and seen photographs. But I also wanted to see the scenery that those women themselves see, so I went around a lot of places by car. Exactly at that time, quite by coincidence I met an artist who I had wanted to meet for a very long time. When I told the curator of the Tsushima Museum who she introduced me to that I was interested in the Ama divers of Jeju Island, the curator provided me with the information that there was a museum dedicated to the Ama divers on Jeju Island, and that I should ask the staff there. That was very kind of her.

When I go to Jeju Island, I hope to use this encounter to broaden my links with other people.

Could you give us an outline of the Grand-mother Island Project that you are working on?

The Grand-mother Island Project traces the memories along the sea route with its center in the Pacific Ocean from Australia to Japan and Korea, and with this as its starting point I am continuing to produce works.

The catalyst for this project was that whenever I am creating my work I always want to proceed with it making the place where I am the reference point. Because I moved to Australia, I decided to make Australia, Japan and Korea the reference points. Looking back on what I have produced so far, I feel that even if the methods of expression and materials I use are different they are all connected to the things that I am interested in. I wondered what the works I have thus far produced would look like if I compiled them together to a certain extent. It was at that point that without deciding on a clear structure I started to work under the title of Grand-mother Island Project.

I have not decided how any chapters there will be. It’s as though there is an island or islands that I’m looking at from afar, but am also rapidly drawing near to. There are individual stories on the island, and though it might be a single island it might also be a group of all sorts of islands. I have proceeded with the project with this sort of image in mind, and have so far completed four chapters.

The first chapter was an installation consisting of textiles with the motif of the shapes of islands seen from the sea. The second chapter was an abstract work on the theme of the spaces between the sea and islands. The third chapter was about the Japanese war brides living in Australia, the US, the UK and New Zealand, and was based on community letters exchanged between these women. For the fourth chapter I produced a work on the theme of the islands of the Pacific Ocean. In the course of this project, I felt that I could not talk without mentioning the connection between the project and the islands of the Pacific Ocean, because I only had a limited and vague knowledge of these islands.

-

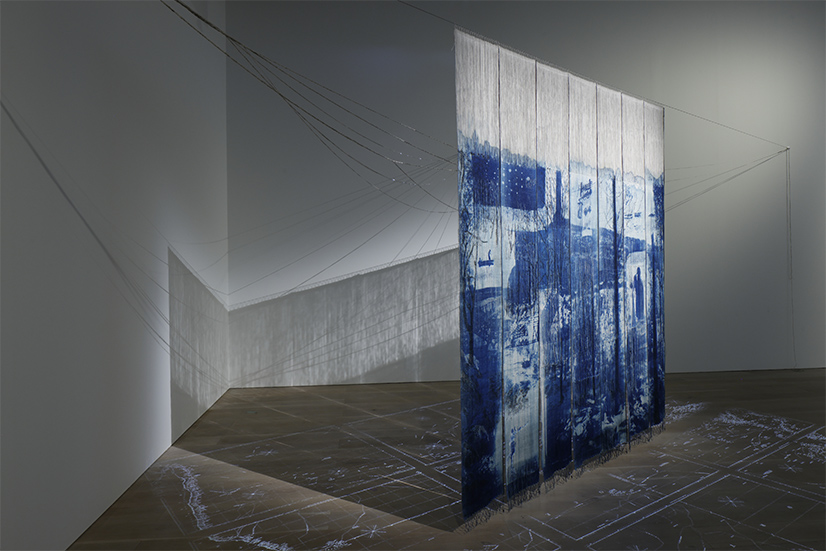

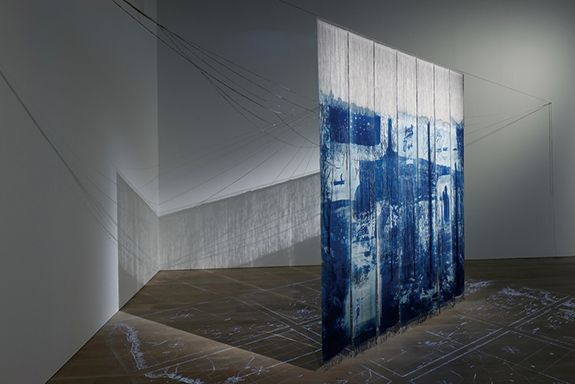

Nautical Map, 2017-2019

Photo: Shinya Kigure

Photo courtesy: Kurumaya Museum of Art, Oyama City -

Floating Forest, 2017

Photo: Masakazu Onishi

Photo courtesy: Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art -

A House of Memory Traces, 2019

Photo: Yuzuru Nemoto

Photo courtesy: Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito -

Seabird Habitats, 2022, installation view at “Roppongi Crossing 2022: Coming & Going,” Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

Photo: KIOKU Keizo Photo courtesy: Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

Could you possibly tell us about the current state of the fifth chapter, which you will be producing from now for the award exhibition?

For the fifth chapter I am thinking about the Ama divers of Jeju Island who I just mentioned. From around the year 1900 the Ama divers of Jeju Island moved around Japan, China and Russia, looking for places to dive for seafoods. That way of life was like going to Japan in one season, Jeju Island in another and Tsushima in still another. I think their movements are also linked to contemporary phenomena. They overlap with the women who go to other countries on their own as laborers. I hope to create the work having researched the orbit of motion of the Ama divers. That is my plan for the fifth chapter.

So it will be somewhat connected with your hitherto exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo.

I am personally looking forward to seeing what appears when all the work form chapter one onwards is collected in one exhibition, and I have a strong wish to show this to the visitors. That’s why I had originally planned to display the works in a compiled manner, but after being in contact with Umeda Tetsuya I am hoping to think flexibly about the planning.