Interview with an award winner

TCAA 2021-2023

TAKEUCHI Kota

Takeuchi Kota worked on volunteer activities in damaged areas in the wake of the Great Japan East Earthquake, after which he moved to reside in Fukushima Prefecture. While working at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant he drew wide attention as the proxy for a “finger pointer worker” who dresses from head to foot in protective clothing and silently points his fingers at the live cameras within the plant. In addition, he also participates in the Don’t Follow the Wind Project, “an exhibition you can’t go to” in which artworks are installed in the inaccessible Fukushima Exclusion Zone created after the nuclear power plant accident.

Takeuchi mainly creates artworks responding to events in Japanese society that have happened recently, for which he was at one time mistaken as a social activist. However, his interests as an artist are always the creation and succession of both personal and group memories, and the pursuit of the emotional impact generated by these. He explores the characteristics of information media that project records and memories and their relationship with people, and through artworks providing pseudo-shared experiences between himself and the viewer he tries to discover human emotions and perceptions.

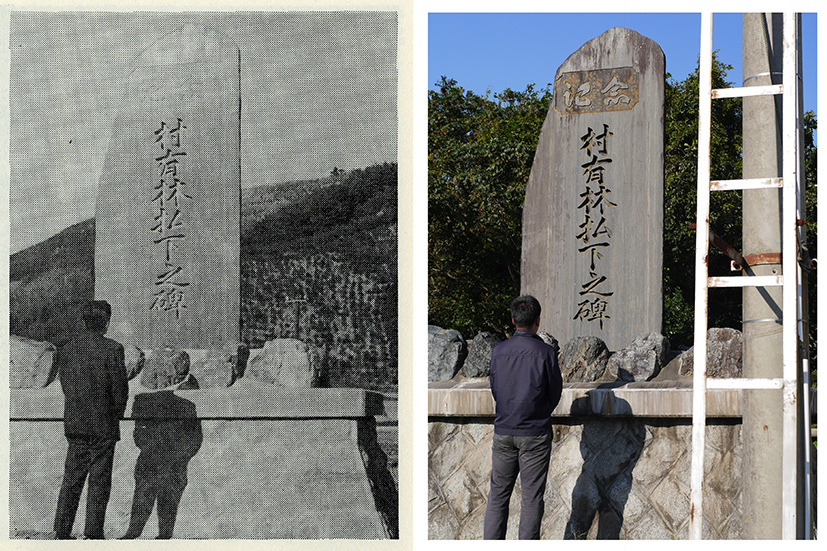

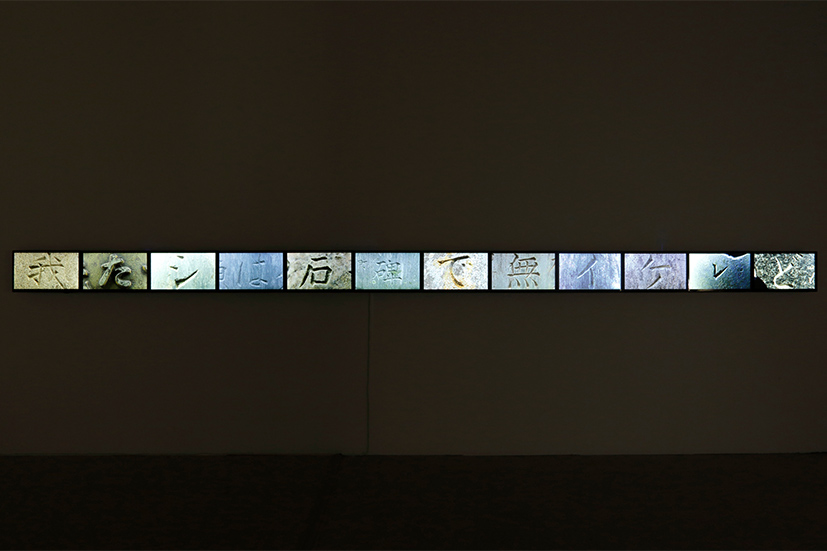

Furthermore, in recent years he has pursued activities that surpass temporal and spatial gaps under the theme of “Parallel, Body, Possession.” For example, the reproduction of stone memorials photographed by local historians, or a typeface font created by a security guard at the Fukushima Exclusion Zone after the nuclear accident. Touching upon the memories of people through buildings, memorial stones, sculptures, official documents, interviews and so on, he has sought to create images using contemporary tools such as map applications, live streaming, and drone cameras. With the aid of a grant from the Asian Cultural Council (ACC) Takeuchi has conducted research in the U.S., and his new work planned for the TCAA will investigate what happened to the balloon bombs that the Imperial Japanese Army launched in the direction of American territory during World War II.

In your latest work you place the spotlight on the correlation between the blindness of the Japanese wartime attacks, which used balloon bombs, and remote weapons up to the latest drone weapons, as well as the violence-impregnated remote communication of SNS and digital media. Today’s interview is being conducted online from the UK, and it appears that you are already eagerly conducting research overseas.

I went to the U.S. again in mid-July. Those who lost loved ones as a result of the balloon bombings, I had wanted to meet them but the 75th anniversary memorial gathering was cancelled due to the COVID-19 crisis and I was left with a feeling that I had missed out on an important part of the process. During my second visit in July I gained the cooperation of local people and was able to actually meet some of the victims. My main objective was achieved and I felt as though the pressure on my chest was somewhat relieved.

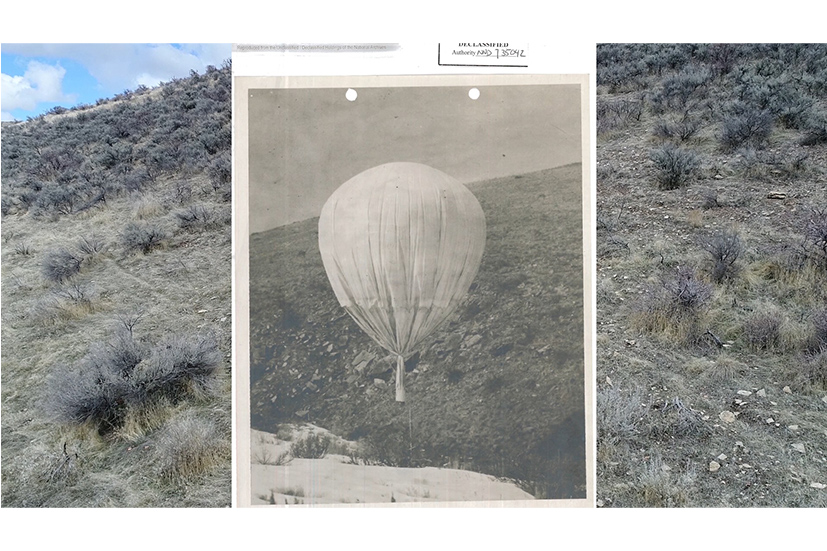

There was also another place I went to investigate. I am trying to recreate the balloon detection and recovery place. I am thinking of incorporating into the viewing experience the perspective of the U.S. intelligence officers and local residents who rushed to the scene when the bombs were dropped. This is to make the viewing experience like a reliving of witnessing the event by incorporating the physical bodies of witnesses and testifiers.

Photographs still remain of the balloon discovered in a mountainous area near to Prosser in Washington, and it was possible to precisely identify the place where it landed by looking at the topography on GoogleMap and the distribution of vegetation. When I actually stood on that point I felt something approaching self-gratification, as if I was confirming something with my own body, engraving something.

That gratification is a sort of spirit of enquiry, isn’t it? Perhaps it would be correct to liken that spirt of enquiry to the Finger Pointer Worker in front of the web camera?

Yes, I think you could look at it that way. Somebody can go there – you can actually try to do this using your own body. A talented artist might be able to wangle some sense of experience without actually going to the place, but this physical approach is my way of doing things.

When I first saw the Finger Pointer Worker I mistook you for some sort of activist making a political message from a social action angle. I have since then rapidly began to appreciate where your interests lie as an artist, not an activist.

It’s certainly the case that for activists, actually going to where the action is taking place helps them make a powerful appeal, so using their bodies is one way of making a testament. I too sought to get to the point where a balloon was dropped and stand there, but once I have the material I shot, the images and photographs or have made an installation, I think about what follows on from that. Of course as a private citizen I have my own political views, but when I step aside from the political nature of a work I start to see what sort of environment and conditions we adhere to. That’s where I feel the significance lies.

With society changing greatly, there is a recent tendency to seek the political and social nature of artworks as a trend of our day and age in which response are being sought from art. I’m interested in the process that led you to link as the subjects for your research the nuclear power station accident, which happened during your own lifetime, and the history of the remote weapons.

There are really fascinating themes, and I think it was my inability to control my own spirit of enquiry, a spirit that made me want to go and check things on-the-spot. I can’t really put it into words, but I just feel something and try to go there. There is a sort of essential part of me there that I cannot hide even from myself. A sense of curiosity, of wanting to see “what’s going on there” may not be considered praiseworthy but I think this candid emotion serves as a common point with the viewer. I think the fact that I act first, while still burdened by the unresolved conflict between my “curious onlooker” temperament and my wish to suppress it, may connect to making me look at the internal conflicts and environments all sorts of people struggle with.

I’d like to ask about the screening process. The screening has been conducted online since the Corona Crisis started, but this time you actually went to the venue at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo and gave your presentation in person.

I don’t possess anywhere that could be described as a production studio or viewing space. My work is sort of experienced-based, consisting of outdoors field research and performance which I take home. If the screening committee had absolutely insisted on visiting me I would probably have suggested meeting in a disused tunnel in my neighborhood.

In my presentation I was conscious of recreating my own experiences in a short space of time. Rather than merely reporting on the past, based on the live happenings on the web camera I considered the best way for a new exhibition plan and online viewing, and on-the-spot before the committee I delivered my presentation using a maquette and web camera. I likened the screening committee members at the venue to visitors at an exhibition, and the screening committee members participating online to visitors watching from home. With regard to the remote attacks, their history and the witnessing of them, I showed how much viewers can become engrossed, and my attitude and concepts regarding contemporary remote technologies. It was highly enjoyable.

We’re talking to each other over a web camera right now, and media and digital technology are an essential part of modern-day creative activities. How do you view the characteristics that they possess?

Strange rumors and conspiracy theories flood the Internet, connections made visible over SNS identify friends or foes like a sensor in a factory, people are whipped by storms of defamatory remarks based on the vaguest of information, and it has now been for a long time that these factors have had an effect on the lifestyle of real society and political conduct. It happens every time there’s a disaster or crime, but personally it was the chaos and divisions that occurred after the nuclear accident caused by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake that really brought this home to me.

Researching the balloon bombs I felt, even more than a wartime topic, a connection with the negative side of the way modern people are behaving now that they have in their hands the remote technologies of the media and Internet. In general I started to feel more strongly that our ethical perspective is being regulated by the technological environment. You could I think say they are being regulated by a “war.” Using the Internet to attack people or organizations you have never met or are acquainted about is akin to “bombing,” The way of thinking that if it’s for the sake of “justice” then a certain amount of errant bombing or “collateral” can’t be helped is like the blind way the Japanese Army released the balloon bombs, or the U.S. Army accidentally kills civilians using drone bombs.

The ethical perspective regarding errant bombing is something that has been slowly cultivated ever since the era of bows and arrows, and is a familiar perspective contiguous with our daily lives. This is because, for example, cameras and monitors are devices that can capture people in remote locations without any physical contact, and then deliver them to distant places over the Internet. I think that remote attack technology will further develop to enable insensitivity towards the pain caused in remote locations. What makes it ideal for weapons are the high precision with which a distant target can be captured, and the way that it does not engender any sense of the reality of killing people. It’s a design that as far as possible removes any sense of hesitation on the part of the person pulling the trigger or pushing the launching button. I think that this is also true of the technological environment around us. I just can’t help thinking that the technologies and ethics surrounding us are developing the foundations for technology to spread in that direction.

Do you feel, on the other hand, that there are any positive directions offered by such media? In the case of your new work, it was because of the media that you were able to find the record of the place where the balloon bomb fell, were able to stand on that spot and express yourself persuasively.

That’s true. Uncovering things buried deep in the earth is one other way of using such media, and it enables me and the people of the future to look back at the crystallization of research by historians and archivists. It can also be used to expose violence and injustice hidden in hard-to-find places, and as a way of linking and bonding those in positions of weakness. I want to try to make an effort not to abandon hope for this, the way that the media should ordinarily be.

I always think that, in addition to guns and weapons, information technologies such as the Internet and social media are not being properly handled by humans, a species that is still very socially and ethically immature. If you drop your guard you could be attacked by your intended victim; if you become scared and run away you’ll be left behind. Takeuchi has picked up the phenomena surrounding this double-edged sword called the media, been emotionally affected by them, and considered them through a process of repeated rumination.

Even ten years after the Finger Pointer Worker, the work continues to powerfully resound. What is still captivating about the work is the raw sense of reality of the accident and the twist on reality seen through the two-layered media of the hazy web camera images. Just how far can one capture the reality that a person in a distant location is experiencing using the superimposing of awareness and imagination with the familiar world that we see through our eyes. What Takeuchi repeatedly sends to us through his expressive activities is a test kit for that ruthless social experiment.

interview, text: SUMIYOSHI Chie