Interview with an award winner

TCAA 2019-2021

SHITAMICHI Motoyuki

Shitamichi Motoyuki’s creative activities continue to be grounded in travel and fieldwork. He continues to use editorial techniques to produce work capturing the contemporary everyday, salvaging the accumulated impact of natural and life processes and forgotten historical realities buried in landscapes. His Forms of War, for which he spent four years investigating surviving military aircraft hangers and gun batteries throughout Japan, and his torii, which explores the contemporary state of relics of Japanese colonialism outside of Japan, are especially renowned. In 2019, he was one of a collective of four, a painter, a musician, an architect, and an anthropologist, chosen to represent Japan at the 58th Venice Biennale. From the first day, his work has attracted attention there.

This award supports the winner’s work for two years. In Shitamichi’s case, those two years will probably pass in a flash. Contemplating the site for his stay overseas, he noted the following:

My work starts in encounters with landscapes, history and local people. After three to five years of exploration and shooting, little by little, the project finally takes shape. For that reason, a long period of support is very helpful. The encounters are always random. Sometimes something interesting happens along the way. In it I discover the seed for a totally different work. To be ready to catch whatever leaps out at me, I want, as much as possible, to leave openings and not be tied down to a fixed formula for work. Of course, I cannot just shoot randomly without being in my intended location. That is why I like to establish a base, a starting point from which to move.

When Shitamichi was a child, he was fascinated by shell mounds. The phenomenon and the landscapes in which they occurred created a connection between the time and place in which he was living and human lives and natural phenomena thousands of years earlier. In art school, he majored in oil painting, but already his starting point was awareness of a desire to see and unearth something in the world around him. He began to experiment with forms of expression combining photography, video, found objects, interviews and events.

From his early period until 2011, the year of the Great East Japan Earthquake, Shitamichi felt indelible doubts about the “history” and “modernity” inculcated in him by his education. He confronted history and landscape through observation, research, and creation (travel, reading, and editing). Following his experience of volunteer work and symposiums in the region affected by the disaster, he began to experiment with exploring the relationship between humanity and nature from a longer term perspective.

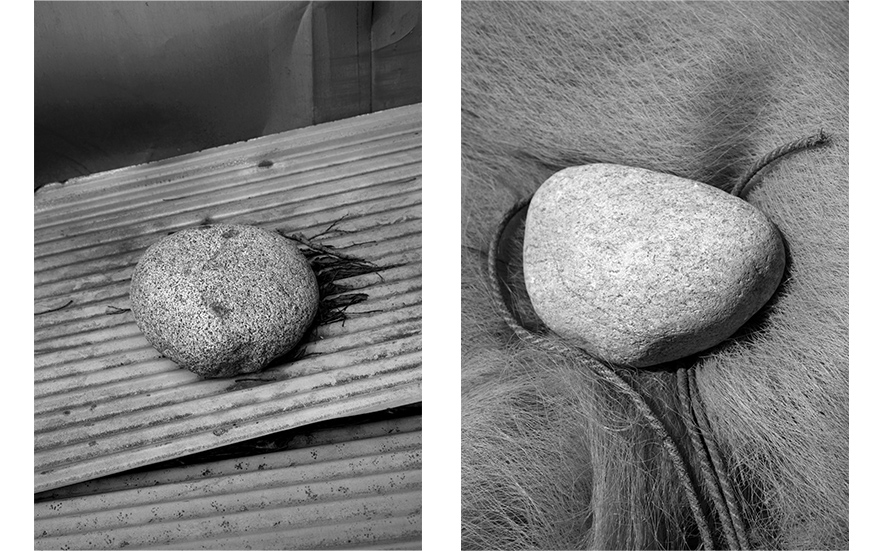

In recent years he has traveled frequently to Okinawa to photograph the giant “Tsunami Boulders” left on the coast by earlier tsunamis. Some of these immense rocks left on land by the Meiwa Tsunami in 1771 and other tsunamis during the preceding six centuries have become objects of worship. Others are now covered with forests. He was moved to begin this work by the debate over whether to preserve a fishing boat washed ashore in one of the towns struck by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, a debate that ended with the boat’s removal in 2013. He says,

As I see it, it is important to consider the shape in which the land is left. Just as I was worrying about how people would react a century from now if that boat were left where it was, I heard about these boulders washed ashore in Okinawa in a tsunami two hundred fifty years ago and how they affect life and nature even now. I became very interested in them.

The historical facts of natural disaster and the evidence that sustains later generations’ memory of it hollow out over time, then take on new symbolic meaning and value. In this respect, we can see a consistent thread connecting Shitamichi’s recent work with the early period series on relics of war and torii. He notes, When someone from a certain era assigns value, it is only a container. To what extent does it weaken the actual value. There we may find a powerful fascination, memories of emotion and doubt, sometimes negative feelings. I was always interested in history but not in the narratives that others wrote about it. I wanted to follow my own direction in learning about it.

Shitamichi’s theme is the spatial and temporal dimensions of everyday landscapes and how value is assigned to them, together with the fluid relationships between history and humanity, nature and humanity, found at their intersections. In his work we find a combination of lyrical subjective expression with an objective, dry, ethnological approach, a distinctive stance toward his subjects rooted in careful observation and research. This award will give him the time to excavate new ground and grow the seeds of creativity he discovers, allowing his work to ferment and mature.

interview, text: SUMIYOSHI Chie